As costs in the Far East rise and consumption patterns change, Egypt tries to position itself – Africa – as the next cheap clothing hub

After nearly seven years in the economic doldrums, Egypt is keen to bolster its clothing exports, worth some $1.4bn a year, and employ over one million Egyptians.

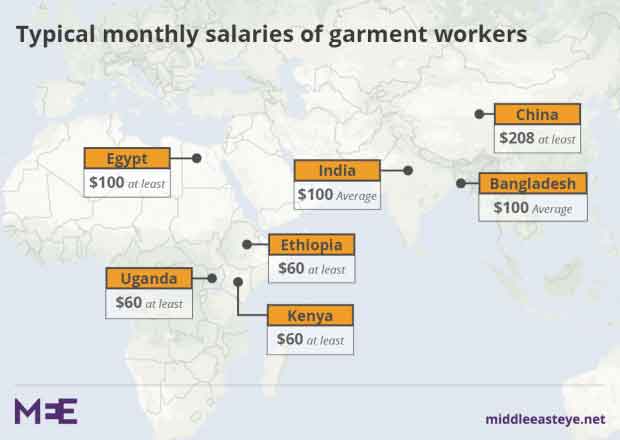

Egypt – and Africa more generally – is well-positioned to become the next destination for sourcing clothing: salaries in the up-and-coming manufacturing hubs of Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya are as low as $60 a month, rising to $100 in Egypt.

What is more, there are no other low-cost destinations left on the planet. Asian manufacturers are at full capacity and South America has also become too expensive to source from.

‘China has become too expensive, while the quality in Bangladesh and Pakistan is not that great’

– Giacomo Romoli, Director of Supply Chain at Guess Europ

Garment workers earn on average $100 a month in India, and around $70 in Bangladesh, while the lowest in China is $208. Bangladesh, the second-largest producer, still has a certain stigma from buyers in the wake of the 2013 Rana Plaza disaster that killed 1,135 people.

That was the message at a major trade conference recently organised by the Egyptian government, export councils and the UN’s International Labour Organisation aimed at promoting Africa as a “new frontier” for garment and textile manufacturing.

Giacomo Romoli, director of supply chain at Guess Europe, who attended the Destination Africa conference in November said, “I’m here to source because China has become too expensive, while the quality in Bangladesh and Pakistan is not that great.

“We already work with Tunisia and Turkey, so we’re here to understand the opportunities.”

With the demand for fast-fashion or “just in time delivery” on the rise – with a garment designed, manufactured and on a retailer’s shelves within a month or less – Egypt in particular is well suited to take advantage of its proximity to Europe, able to export in less than 10 days, and to the USA, in 14 days compared to 35 days from Shanghai.

“There are 1.1 billion Africans, so it is the next frontier, with a huge population, while the average age is 19 years old today,” said Jaswinder Bedi, chairman of the Export Promotion Council of Kenya at the conference, which was held at the Nile Ritz-Carlton.

“We will be the factory of tomorrow due to demographics.”

‘Next migration’

Egypt is already a major manufacturer for brands like Zara, Calvin Klein, Decathlon and Tommy Hilfiger.

By 2015, garment exports had reached $1.4bn when buyers were warded off in the wake of political instability following the 2013 overthrow of Mohamed Morsi and the election of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in 2014.

Now the country is trying to get back to pre-revolution levels, when it had annual growth of some 22 percent from 2006-2011, according to the Ready Made Garment Council. The sector is a major employer, with anywhere from 300,000 to 1.5 million employed in 1,500 garment factories, and 15,000 textile factories, around a third of which are government-owned.

To increase their wages by as little as $3 per month, Egyptian garment workers have been shifting from one factory to another in search of better pay

With Egypt’s population growing by 3 million a year to 93 million, 28 percent living in poverty, and an official unemployment rate of 12 percent, there is a huge pool of “human resources” to draw on, while salaries in the garment sector typically range from $100 to $113 per month.

The depreciation of the Egyptian pound from eight EGP to the dollar in 2016 to nearly 18 EGP in November 2016 has also made Egypt a cheap sourcing destination.

But what’s good for companies has been hard for Egyptians: depreciation has pushed up the cost of living, with food and average inflation rising from 13.8 percent in October 2016 to 42 percent in August 2017, according to the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation.

To increase their wages by as little as $3 per month, Egyptian garment workers have been shifting from one factory to another in search of better pay, forcing some companies to increase wages to compete.

Chinese and Egyptian employees work together at the Chinese-owned Nile Textile Group factory in Port Said (AFP)

“In the first year we had a turnover of 1,000 workers, so we now pay $130,” said Samih Sousa, general manager of Cotton & More, a Syrian company which set up operations in Egypt in 2012.

While Egypt has attracted Syrian companies like Sousa’s as a result of the conflict, it has also become an attractive manufacturing for Turkish companies – the world’s third-largest garment manufacturer – to take advantage of low-cost production and Egypt’s preferential export deals with the European Union and the US.

Egypt can export to the US tax-free if garments are made at Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZ), which requires 10.5 percent of manufactured goods to be sourced from Israel.

US President Donald Trump’s scuppering of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement in January, which would have allowed greater free trade between Asia and North America, has also been a boon.

“What is happening is that with no TPP, Africa as a whole needs to absorb what I call the ‘next migration’, as manufacturing went to Asia, and now it will come to Africa,” said Waleed el Zorba, managing director of Nile Holding Company.

Changing consumption patterns

As middle classes in China and India grow, Egyptian and African manufacturers are also banking on changing consumption patterns. Currently, the total garment market size of the US and Europe is $674bn, while it is $326bn in China and India combined.

“That tells you the biggest market is the West, but consumption is changing rapidly,” said Bedi.

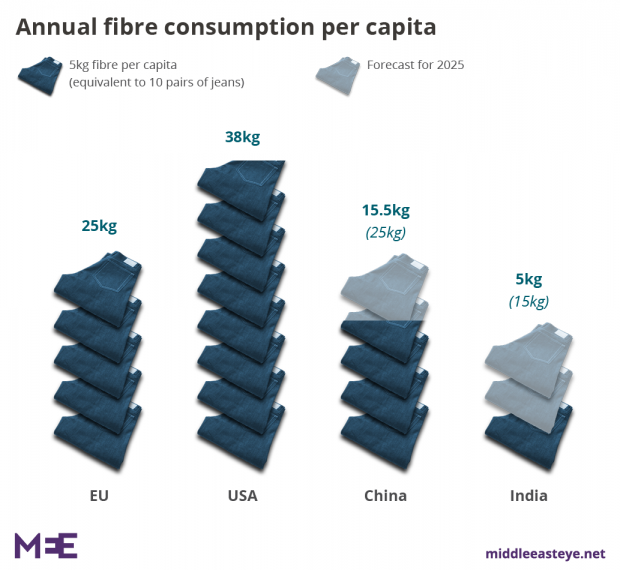

Annual per capita fibre consumption – clothes, sheets, towels, jumpers, jackets – in the US is currently 39 kilograms, and in the EU 25 kilograms – or the equivalent of 78 and 50 pairs of jeans respectively.

In China, it has surged from 5kg a decade ago to 15.5kg today, and forecast to reach 25 kg by 2025. Per capita consumption is expected to surge in India from 5 kg to 15kg.

By 2025, India and China’s consumption – with a combined population of 2.66 billion or around 36 percent of the world’s population, according to the UN – will have reached $740bn, outstripping the US and the EU’s $725bn.

The expectation is that China and India will source clothing domestically and closer to home, leaving Africa – and specifically North Africa – ripe for opportunity.

“We can’t prove that buyers are leaving Asia, but from 2016 there is demand for sourcing clothes closer by,” said Dhyana van der Pois of the International Apparel Federation (IAF), whose clients include G-Star.

The key for Egypt and African manufacturers to develop is to source within the continent, and take advantage of regional free trade agreements, as less than 11 percent of trade is inter-regional. By comparison, 60 percent of EU trade is within the EU.

Tunisian and Egyptian trade is a stark example. Tunisia imports only 1.3 percent of textile and clothing imports from Egypt, compared to 19 percent from France, and 23 percent from Italy. Tunisia exported just 664 tonnes to Egypt in 2016, while Egypt exported 5,024 tonnes to Tunisia, according to the Confederation of Tunisian Citizen Enterprises (CONECT).

Less than 11 percent of trade in Africa is inter-regional. By comparison, 60 percent of EU trade is within the EU

Egypt’s plans – and challenges

Under Egypt’s Vision 2025, it aims to create one million jobs in the textile and garment industry, train some 750,000 workers, supervisors and managers, and attract $13.5bn in local and foreign investment.

It’s a tall order, but by October, Egypt’s garment sector had already grown 14 percent this year, ahead of projected growth forecasts and is expected to reach $1.4bn, a return to pre-crisis levels.

Still the country faces a Catch-22. The sector needs to mechanise to better compete with the likes of Turkey and move away from being a “cut and sew” hub to have more complicated pieces that can fetch higher prices. That however involves more automated production and would require fewer employees, and Egypt needs more people to be employed.

One aim of the government is to bolster cotton production, known as “white gold” as a result of its high-quality long-thread count. Egyptian cotton is nearly double the price of ordinary cotton.

There would seem to be room to grown: only 10 percent of all cotton used in Egypt is locally sourced and there have been problems with fake Egyptian cotton being sold around the world.

“It was all over the world in terms of fakery,” said Wael Olam, chairman of the Cotton Egypt Association. Egypt has implemented a traceability auditing test to counteract this issue and encourages the use of a Cotton Egypt logo.

Yet with international demand for both man-made and natural fibres at 78 million tonnes, and cotton production only 24 million tonnes globally, Egypt and other African manufacturers will focus on synthetics.

“Synthetics and polyester will grow. It doesn’t mean cotton will die, but it will become a luxury item,” said Bedi, the Kenya export council chairman.

There is another problem: the more cotton produced for export, the less food is produced. Egypt is currently the world’s largest wheat importer, while its food production is also export orientated.

A further issue is that while the ILO is working with Egypt to boost cotton production, it is very water intensive, requiring 20,000 litres to produce just 1kg – equivalent to one t-shirt and a pair of jeans, according to the WWF. Egypt is already facing chronic water problems, expected to consume a third more water than is available by 2020.

As Abdel Latif Khaled, head of the reservoirs and grand barrages sector at the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation told Youm7, “Egypt does not have the luxury to waste even one cubic metre of water.”

‘Do it right’

For all of the potential opportunities, participants at Destination Africa were keen to emphasise that they don’t want a “race to the bottom” on wages.

“We don’t need to build sweatshops like in Asia, but learn from their mistakes and do it right,” said Bedi.

Improving conditions for workers in the country, however, would seem to be a challenge.

This year, the ILO implemented its Better Work programme in Egypt – the second in the Middle East after Jordan – to improve working conditions. Out of 1,500 garment factories, it is currently working with 26.

‘We don’t need to build sweat shops like in Asia, but learn from their mistakes and do it right’

– Jaswinder Bedi, Chairman of the Export Promotion Council of Kenya

But out of the 10,000 state-owned factories – the majority of which produce textiles, not clothing – all turned down the ILO’s request to work with them.

“We went to one public company, but they wouldn’t cooperate. So we are not working with them as they would not commit to change,” said Adnan Alrababh, chief technical advisor at the ILO in Egypt.

The ILO’s tripartite structure is also not able to work effectively in Egypt. The system is designed to incorporate the views of the government, employers and employees to address labour issues at the ILO’s annual meetings.

Although a draft law is being mulled, unions are not allowed in Egypt and workers in state-owned enterprises have minimal recourse for appeal when their employer is the government, which has a less than stellar human rights record.

An Egyptian worker rides his bicycle near the Misr spinning and weaving factory in Mahala, 120km north Cairo (AFP)

In its latest survey, 71.3 percent of the 174 Egyptian factories audited by Sedex, a non-profit organisation dedicated to improving global supply chains, were non-compliant with health, safety and hygiene standards, significantly behind the 1,172 factories in other African countries, at 47.11 percent.

Egypt’s clothing production is slated to reach $2.05 billion by 2021, according to Euromonitor International.

If garment manufacturing takes off in the rest of Africa, Egypt will be in a strong position to be a continental leader and hub – a major reason the trade event was held in Cairo. But for that to happen, greater inter-Africa trade needs to truly develop.

“We need to really work together on one, changing our mindset from competition to cooperation, and two, build a continental value chain where everything is available,” said Mohamed Kassem, commissioner of Destination Africa, and the former chairman of the Garment Export Council.

“Forget about the division of north and sub-Saharan Africa, that’s an artificial division created by the West. We need to really integrate all textile producers in the continent.”

Source: www.middleeasteye.net