Textile archaeologists:::::From clay artifacts, scientists learn how fabrics were made long ago

Norse sails loomed off the shores of the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, along the northeastern coast of Great Britain, on June 8, 793. The seafaring invaders sacked the island’s undefended monastery.

The Viking Age had begun.

For more than 270 years, the sight of red-and-white-striped Viking sails heralded an incoming raid. Those mighty sails that drove the explorers’ ships were made by craftspeople, mostly women, toiling with spindles and looms.

“There would have been no Viking Age without textiles,” says archaeologist Eva Andersson Strand, director of the Centre for Textile Research at the University of Copenhagen, in old Viking territory.

Yet textiles have not received much attention from archaeologists until recently. Andersson Strand is part of a new wave of researchers — mostly women themselves — who think that the fabrics in which people wrapped their bodies, their babies and their dead were just as important as the clay pots in which people preserved food, or the arrowheads with which hunters took down prey.

These researchers want to know how ancient spinners and weavers, from Viking territory and elsewhere in Europe and the Middle East, fashioned sheep’s coats into sails — as well as diapers, shrouds, tapestries and innumerable other textiles. Since the Industrial Revolution, when fabric crafts migrated from hearth to factory, most people have forgotten how much work it once required to create a tablecloth or wedding veil, or 120 square meters of sailcloth to propel a longboat across the water.

Ancient art depicting female textile workers, as on this Greek oil flask from about 550 B.C., supports the idea that spinning and weaving were primarily women’s work.

Textile making is “one of the major industries, and always has been,” says Lise Bender Jørgensen, an archaeologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. Today, the annual global market for yarns and fabrics is worth nearly $1 trillion.

Before the 1764 invention of the mechanical spinning jenny, people twisted fibers — flax or wool, for example — together by hand to spin a strong thread. The person doing the spinning would pinch a few strands from a mass of fibers and hook it to a hand-length stick called a spindle. A small, round weight, called a whorl, helped the spindle turn. By dangling the turning spindle, the spinner could twist the fibers into long threads.

Weavers then attached these threads to a loom, crisscrossing the fibers. That mesh could be loose and open, or tight and dense, depending on the fabric desired.

People have been using fibers for millennia, for string and rope as well as thread, and probably started spinning around the fourth millennium B.C., says Margarita Gleba, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge. Loom-based weaving, which evolved from basketry, happened as early as the seventh millennium B.C. in Turkey. Back then, the threads were made by splicing.

The ancient textile industry has been difficult to study. Unlike pottery or arrowheads, organic textiles rapidly degrade. Archaeologists interested in what people wove and wore in the past make do with scraps of material preserved by luck — for example, if the fabric happened to be buried in bogs or salt mines.

While some researchers have analyzed the bits of fabric they can find, Andersson Strand is more interested in the production process and its context — the cultural and economic impact. She wants to know what life was like for the people who made textiles thousands of years ago. How much of women’s time was taken up with spinning and weaving? Did textile workers specialize in one part of the process? And did techniques vary by culture?

To understand the work of European spinners and weavers from centuries past, she has turned to the remains of tools that once created those fabrics. Made of clay, stone or bone, the whorls that twirled the spindles and the loom weights that kept the threads taut during weaving are abundant at many archaeological sites.

Andersson Strand uses experimental archaeology to learn what kind of threads and fabrics — fine or coarse, dense or airy — would result from different tools. Her findings are helping archaeologists infer from the leftover tools what textiles people might have created and traded.

Katrin Kania, a textile archaeologist based in Germany, shows how a spinner makes thread. Here, she pinched a bit from a mass of fibers, attaching it to the spindle in her right hand. A whorl at the spindle’s bottom helps the tool spin and create thread.

“She’s really made the textile tools speak,” Bender Jørgensen says. But not all scholars agree that the tools determine the fabric. Some researchers suggest that the individual crafter, inaccessible to archaeologists, was a more important factor in how spun threads turned out.

In the pits

Andersson Strand built her first loom in 1988 as an archaeology graduate student at Lund University in Sweden. Archaeologists had excavated loom weights from several Viking pit houses, which had no windows, just a hole in the roof. Andersson Strand wondered whether it would have been possible to weave with the only illumination coming from a single skylight.

She constructed a loom like the Vikings would have used, a warp-weighted loom. The vertical threads of a woven fabric are called the warp, and the horizontal strands are the weft. Loom weights attached to the warp threads hold them down, providing tension. The weaver passes the weft threads back and forth, over and under the warp, to create the fabric.

Researchers in Slovakia built a warp-weighted loom to weave a twill fabric like one that dates to between 800 and 400 B.C. found in the Hallstatt salt mines in Austria. Loom weights (left, shown dangling at the loom’s base) hold the vertical threads taut.

With the loom, Andersson Strand got down into a cellar-like pit reconstructed by students and started crafting. “Those houses were excellent for weaving, actually,” she says. Plenty of light came through the skylight. The effort helped convince her to focus on textile tools as a window into the world of ancient fabrics and the people who made them.

“People thought I was quite crazy,” she says. At that time, archaeologists didn’t think much about whorls and loom weights as functional objects. Researchers didn’t record crucial details, like weight and width, and sometimes tools were misclassified.

Andersson Strand wrote to one excavation director to ask if she could study textile tools found at the site — not only whorls and loom weights but also other rarer specimens such as the wool combs used to align fibers before spinning. The director welcomed Andersson Strand but warned her that he had no idea if wool combs had been found at the site. “I didn’t know that tool existed,” she recalls him saying.

Nonetheless, she amassed a dataset of more than 10,000 different tools, mostly loom weights and spindle whorls, from several sites in Sweden and one in Germany, from the years A.D. 400 to 1050.

Andersson Strand found some surprises at a Viking trading center called Birka, thought to have been the first real town in what is now Sweden. It’s likely that the local king ordered Birka built in the mid-700s on an island west of modern-day Stockholm. Traders visited from Europe and beyond, bringing beads, Arabic silver and other goods(SN: 4/18/15, p. 8). Birkans, in return, offered iron and furs.

Andersson Strand predicted that Birkan textile workers would have spent their time — a lot of their time — spinning and weaving coarse fabrics, such as sailcloth. Finer fabrics probably arrived via trade.

But at Birka, she found a puzzling range of tool sizes and weights, and tested what the ancient whorls could do. Because today’s tools and textiles are different, Andersson Strand recruited textile crafters trained in ancient techniques to test replicas of the ancient tools.

She discovered that the heavier the whorl, the thicker the resulting thread. That finding makes sense: Heavy whorls would snap thin threads; lightweight whorls wouldn’t turn properly when dangling from a thicker thread.

Tool makes the textile

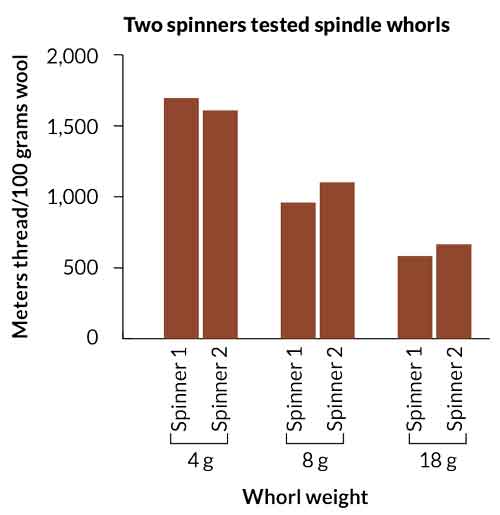

The size of the spindle whorl determined the length of thread that two spinners independently produced. For both spinners, the lighter whorls produced longer, thus thinner, thread.

Andersson Strand reported in her 2003 book, Tools for Textile Production — From Birka and Hedeby, that because Birkan sites contained such a wide range of tools, Birkan weavers must have created a broad repertoire of threads and fabrics — both coarse sailcloth, as she had predicted, and the fine material, presumably remnants of clothing, found in nearby graves.

Turning back the clock

From the Viking Age, Andersson Strand turned her attention further back in time to the Bronze Age, between 3000 and 1100 B.C., and farther south to the Mediterranean. She and collaborators collected data on 8,700 tools from 29 sites in Europe and the Middle East.

The researchers wanted to reproduce the full process of textile manufacture, from raw fibers to woven fabrics. Because the final product could be influenced by the fibers, the tools or the individual crafters, the team recruited two craftswomen to see if each created different textiles.

The crafters started with Shetland wool, thought to be closest to that used by Bronze Age spinners. For tools, a ceramicist re-created cone-shaped whorls in three weights: four grams, eight grams and 18 grams (about the weight of seven pennies). These proportions were based on clay whorls found in Nichoria, a Bronze Age site in Greece. The two spinners produced similar woolen thread, with the lighter whorls making thinner threads.

Next, the craftswomen turned to weaving. They arranged some of the threads they had made on a warp-weighted loom, using reconstructed weights, based on ones from Turkey. The women were asked to make a simple tabby weave that was common during the Bronze Age. In a tabby, or plain, weave, each weft thread goes over one warp thread and under the next, then over and so on across the fabric. The next weft thread reverses the pattern.

The two spinners made similar fabrics from the woolen threads, Andersson Strand and colleagues reported in a 2015 book, Tools, Textiles and Contexts: Textile Production in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age. The tools and materials, not the crafter, seemed to be the crucial factors determining the final product.

In both the Viking and Bronze Age experiments, crafters kept track of how long the work took. From that data, Andersson Strand estimates it would have taken four women, working 10-hour days, a full year to spin and weave 120 square meters of fabric for one large Viking sail.

From tools to textiles

With these experiments, tools left lying around ancient workshops are telling their stories. Archaeologists can figure out what fabrics could have been woven, even though not a thread remains. The heft of a loom weight reveals how many threads it could have held; the width of the loom weight indicates how closely spaced those strands would have been. Based on their analyses, Andersson Strand and colleagues developed methods to work from loom weight to fabric type.

“We can never say it’s exactly this fabric or that fabric, but we can give the range of fabrics that could have been produced,” Andersson Strand says. For example, a particular loom weight found in Turkey and dating to 3800 to 3350 B.C. weighs 870 grams, a bit lighter than a quart of milk. Andersson Strand and colleagues calculated it would have been suitable for a coarse fabric made with thick threads. Another loom weight from 1750 to 1300 B.C. Turkey — which weighed 177 grams, comparable to a cue ball — would work best with thinner threads requiring low tension, the group reported in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology in 2009.

That’s only a starting point for the kinds of questions Andersson Strand wants to address. “It’s more what the textiles tell us about the society — that is what really fascinates me,” she says.

She recently analyzed loom weights from the Greek island of Crete to learn what textiles might have been made or traded at three palaces dating from 1900 to 1700 B.C. Based on the tools present at a palace site in Knossos, workers there probably used thin threads to make dense fabrics. Weavers in a palace in Phaistos probably worked with a wider variety of threads, mostly fine ones, and had to cram the horizontal weft threads tightly to make solid cloth. And from a palace in Quartier Mu came a range of textiles, Andersson Strand reported in 2018 in the Proceedings of the 11th International Cretan Congress.

The use of fine threads suggests that workers needed high-quality, well-prepared wool or flax. But archaeologists haven’t found many spindle whorls at these three sites. Perhaps, Andersson Strand and colleagues speculated, the Cretans did their spinning elsewhere. That would fit with ancient writings suggesting that textile workers were specialized — spinners and weavers toiled separately.

Other researchers are using Andersson Strand’s methods to infer past textiles from excavated tools at other sites. Gleba has been analyzing the textile industry of Italy and Greece of the first millennium B.C. The Greeks used lighter loom weights than Italians did. The lighter weights would have been appropriate for tabby weaves. The bigger, heavier Italian weights could have been suited for a technique that creates diagonal ridges, for a more complex twill fabric. Gleba examined textile scraps, mostly from graves, that support the weaving patterns suggested by the tools, as she reported in 2017 in Antiquity.

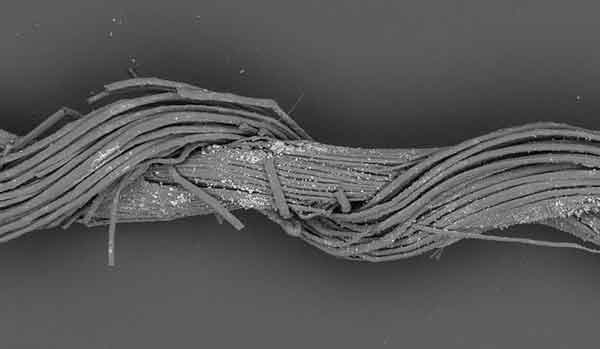

Loom weights suggest Italians made twills, like this from the seventh century B.C. (left); Greeks, instead, made simpler tabby weaves, like this from the fifth century B.C. (right).

Spinning for science

Of the three factors that influence a final textile, Andersson Strand thinks the tools and materials are more important than the person doing the work. But Katrin Kania, a freelance textile archaeologist in Erlangen, Germany, thinks the textile worker is most crucial to spun threads.

A spinner herself, Kania says, “I spin a thin yarn almost no matter what [tool] you hand me.”

So Kania conducted her own experiments, recruiting 13 experienced volunteer spinners, plus one beginner. Kania purchased two different kinds of wool, German Merino and Tyrolean Bergschaf, to test the influence of raw materials.

She provided five different spindles, varying the weight and dimensions to change how they turned. Participants called one tool, with a thin clay cylinder for a whorl, the “spindle from hell” because it required constant flicking to keep it in motion.

Kania asked the spinners to create whatever thread felt natural with each tool, and then she gathered the products to analyze thickness, length, evenness and twist angle. The different types of wool didn’t make much difference to the final product. Nor did the spindles.

But the individual spinner did have an effect; each volunteer stuck to a personal range of yarn thickness regardless of the tool, Kania reported in 2015 in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. “The spinner is the main factor of what comes out,” she says.

Katrin Kania compared threads created with five different spindles. The middle spindle was the hardest to use, earning the nickname, “spindle from hell.”

Tereza Štolcová, a textile archaeologist at the Institute of Archaeology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Nitra, agrees that the tool alone doesn’t predetermine the thread. But she thinks the tools do matter and that Andersson Strand’s calculations are helpful for narrowing down what textiles people might have created in the past — so long as researchers understand the estimates offer only a range of threads or fabrics possible, not a certain deduction.

Andersson Strand doesn’t deny the role of the individual craftsperson in the final product. But, she notes, it’s important to consider the ancient textile worker in context. It wouldn’t be practical for one woman to spend four years creating a sail on her own; instead several women would need to work together. To do that, they would need consistent threads and consistent weaves. The way to achieve that would be for everyone to use the same version of a tool in the same manner.

Weaving a tapestry of the past

Between the tools and the textiles, archaeologists are building a picture of life for the ancient European textile worker, and how those fabrics might have been used. That worker was most often a female, based on ancient artwork that depicts women spinning and weaving, historical writings and the presence of textile tools in women’s graves. But men and children were probably involved at times, Gleba says.

If the weaver were a Viking, she might have spent long days in a pit house, passing the weft threads back and forth to make all the fabrics needed in her community. If she lived in a Greek palace, she might have ordered prespun threads of fine quality. She probably specialized, focusing on just spinning or just weaving. Women may have worked side by side to produce wider fabrics on large looms.

Wherever she worked, she was highly skilled and very busy. And chances are she carefully selected the right tools for the fabric she was making.

Not all textiles would have required specialists; there would have been a thriving home-based industry as well. To fuel a community’s need for textiles, hand spinners might have carried a spindle everywhere, turning to it at any spare moment — much like people today with their smartphones.

The earliest textiles

While most textiles degrade before archaeologists get a glimpse, occasional scraps survive to offer clues to how they were made.

The first threads were not spun with a spindle, but spliced together by hand, says archaeologist Margarita Gleba of the University of Cambridge. Stone Age weavers used long plant fibers — such as flax, hemp or nettle — that could be layered together or joined end to end. Only after 4000 B.C., when crafters started using wool with its shorter fibers, did spinning become necessary, Gleba says. Some craftspeople still use splicing in Asia, and though the technique was discontinued in Europe, it lasted longer there than scholars had once thought. In May in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, Gleba reported finding spliced fibers in European textilesmade during the Bronze Age and into the first millennium B.C.

The earliest preserved woven textiles were dug up at the Turkish site of Çatalhöyük, which was inhabited from about 7100 to 5950 B.C. These scraps, described in the 2018 Archaeological Textiles Review, were preserved by fire: They were buried beneath the floors of houses that later burned, which converted much of the textile to pure carbon, which was less likely to degrade.

The scraps are plain tabby weave from spliced plant fibers. Turkey also hosts some of the oldest loom weights ever found, including 11 clay, doughnut-shaped ones unearthed at the site of Ulucak. Together, these finds indicate “that somebody had invented the loom, [by] sometime in the middle of the seventh millennium B.C.,” says archaeologist Lise Bender Jørgensen of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. — Amber Dance